Exploring Faith 2022 - Revd Dana English - Hildegard Von Bingen

How to sum up the importance of a figure such as Hildegard of Bingen? One scholar said this: “St. Hildegard of Bingen, also known as the ‘Sybil of the Rhine,’ was one of the most remarkable women of the 12th century. She was a visionary theologian, prophetic reformer, composer of remarkable music that soars up to the heavens, natural scientist and healer. She was declared a Doctor of the Roman Catholic Church in 2012.” 1

Another said this: “The bearer of a unique and elusive visionary charism, she was also a prophet in the Old Testament tradition—-the first in a long line of prophetically and politically active women—yet at the same time a representative of the German Benedictine aristocracy in its heyday. Proudly aware of belonging to a social and spiritual elite, she was profoundly humble before God, awed by the audacity of her own mission, and by turns diffident and strident about her gifts. Measured in purely external terms her achievements are staggering. Although she did not begin to write until her forty-third year, Hildegard was the author of a massive trilogy that combines Christian doctrine and ethics with cosmology; a compendious encyclopaedia of medicine and natural science; a correspondence comprising some 400 letters to personages such as emperor Frederick Barbarossa, King Henry II and Queen Eleanor of England, and four popes. She preached sermons from 1158 onward, not something women did in that period; she wrote astonishing liturgical music and hymns and even a musical morality play (the Ordo Virtutum).” 2

Let me give you a short outline of the events of her life, and then try to hint at some of the theological themes that were most important to her. The largest and most influential house of the Benedictine order was the Abbey of Cluny, in Burgundy, founded in the year 910. In the same year that Hildegard was born, 1098, almost two hundred years later, a group of Benedictine monks founded Cîteaux Abbey, with the goal of following more closely the Rule of

Saint Benedict. Bernard of Clairvaux entered that monastery in the early 1110s with thirty companions and helped to establish the order. By the end of the 12th century, the Cistercian order had spread throughout Europe. These reformist monks tried to live monastic life as they thought it had been in Saint Benedict's time, and in some points they went beyond it in austerity. The most striking feature in the reform was the return to manual labour, especially agricultural work in the fields. But in the Cistercian Abbey in Germany in which Hildegard grew up, the monastic life was still one with close ties to the aristocracy as founders and patrons, and the pattern of daily life was not harsh. Born into a family of the lesser nobility, a family of wealth and large

connections in society, in Bemersheim (the western part of Germany, the Rhineland—-near Worms, slightly southwest of Frankfurt), Hildegard, as the

last of ten children, was pledged as a tithe to the service of God at the age of eight. In 1112, in the Abbey of Disibodenberg, she was placed in the care of the daughter of the Count of Spondheim, named Jutta, who had made the decision to become a recluse there. The two families were close, and Hildegard became the companion, helper, and pupil of Jutta. In order to participate in the divine office and read the Bible, Hildegard acquired a basic knowledge of Latin in order to understand the liturgy she recited each day. Boys of her social standing would have received a far better education at a cathedral school. Hildegard did not know German; her Latin was neither literary nor polished. Nevertheless, over the course of her life she exhibited a wide range of learning, not only in the Scriptures but in classical Latin literature, Neoplatonic philosophy, and natural science.

She was helped immensely in the work of writing down her later visions by Volmar, a monk who was both learned in theology and congenial to her in

temperament. He offered her his unvarying support, not from a position of superiority over her, but as a helper and friend. Her other close friend became Richardis von Stade, a young nun, another source of great emotional support. She, also became an invaluable assistant to Hildegard. When Jutta died in 1136 Hildegard was elected prioress. She was 32. Hildegard had suffered from headaches and ill health from an early age. She had begun to receive visions at the age of five. It was not until she was 42, however, that she received the instruction to write down her visions, along with their interpretation.

The visions she received came not during trances, ecstasies, or seizures. She always insisted that she ‘was fully awake in mind and body.’ Unlike some

others of that period, she did not engage in nor counsel extreme fasting or mortifications, and did not spend long periods in private prayer. “It took

decades of painfully acquired self-knowledge—-and the authority of an abbatial position—-before she was able to understand the visions as a vehicle for divine revelation.” She was instructed not to waver in her sense of unworthiness as a woman or as someone untaught, for hers was a Divine authority. God had chosen her as His own medium of revelation, and she was to fully claim the authority that this fact gave her. Her almost constant illness gave her a

balancing sense of her own frailty and dependence upon God. Hildegard’s prophetic call was received in 1141. It came in the form of a fiery

light that filled her whole heart and brain and gave her a penetrating knowledge of all the books of Scripture. She knew that she had not received this call

because she was any more deserving than others, but because the times were desperate. She described the age in which she lived as ‘effeminate’—-“one in

which the the Scriptures were neglected, the clergy ‘lukewarm and sluggish,’ and the Christian people ill-informed. Her mission, then, was to do with her

prophetic charism what professional clerics had failed to do with their priestly charism: teach, preach, interpret the Scriptures and proclaim the justice of

God.” 3

In 1148 Pope Eugenius, himself a Cistercian, at the urging of Volmar, Hildegard’s bishop, Henry of Mainz, and Bernard of Clairvaux, gave his official

endorsement to her work. This made a tremendous difference to her in terms of her confidence and her sense of protection against future censure for preaching and writing as she knew she was called to do, but as a woman. Hildegard was also, by temperament, of a strong character. She held firm,

opposing her own abbott, in order to relocate her abbey to Rupertsberg in Bingen am Rhein, in order not to have any spiritual or financial dependence

upon the monks of St. Disibod. When her dear friend and helpmate Richardis decided that she wanted to leave the Abbey to become prioress in another—

Bassum, Hildegard did everything in her power to keep her from leaving. That battle of wills was only resolved, sadly, by Richardis’s untimely death.

During the 1150s Hildegard engaged herself in an astonishing burst of sustained activity. She supervised construction of the new buildings of the new

monastery, secured gifts and bequests to enable it to be financially secure, established monastic discipline there through preaching and teaching, wrote a

commentary on the Athanasian Creed, composed her music. The final version of her music drama, the Ordo Virtutum, was written in this period. It antedates other known morality plays by about a century and a half. She also created a lingua ignota, a sort of secret language, in order to instil a sense of mystical solidarity among her nuns. Her growing fame brought an ever-widening stream of pilgrims to the monastery, as well as those seeking her counsel and those seeking to become nuns under her care.

Around 1158 she felt that things were well-established enough at Rupertsberg for her to undertake prolonged absences on three long preaching tours. She

travelled along Germany’s major rivers, the Rhine and Maine, preaching at monasteries and at Cologne and Trier, delivering fiery apocalyptic sermons.

Many requests were made for the transcripts! Despite constant ill health, Hildegard persisted not only in her preaching but also in her writing.

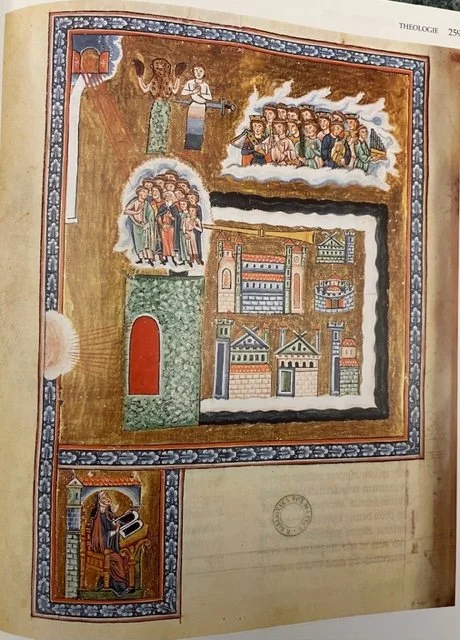

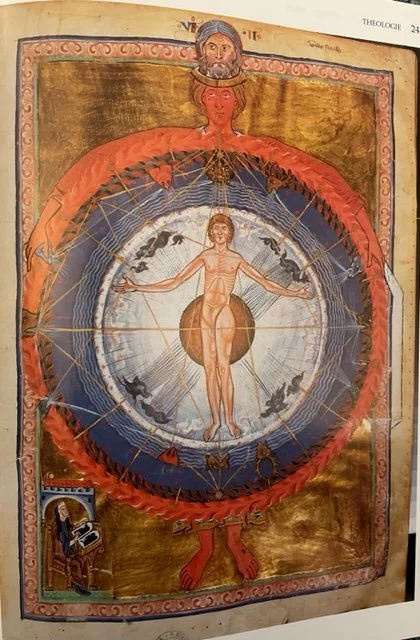

She died at the age of 81 in 1179. The works she left us are wide-ranging. She wrote on healing and herbal medicine (The Book of Simple Medicine, also called Nine Books on the Subtleties of Different Kinds of Creatures, and Causae et Curae or The Book of Composite Medicine). She claimed no divine inspiration for these: they were the product of her own curiosity and experimentation. Her major theological treatises are three. The Scivias was completed in 1152 after ten years of work. The title is a contraction of the verse Jeremiah 5: 4—- Scito vias Domini—“Know the ways of the Lord.” (taken out of context) Hildegard, in choosing this title, was conceiving of herself as an apocalyptic prophetess who was appointed to call God’s people back to paths of righteousness and true devotion. One scholar commented that if Hildegard had been a man, the Scivias would have been considered one of the most important early medieval summas. Each book of the Scivias consists of several visions and Hildegard’s careful interpretation of their meaning. Of the six visions that comprise Book One, the first deals with Creator and Creation. The second deals with the Fall, the third with the whole cosmos, the fourth with the human soul and body, the fifth with the synagogue, the sixth with choirs of angels.

Book Two contains seven visions relating to Redemption— those of Christ, the Trinity, the Church, the sacrament of confirmation, the three orders in the

Church—-religious, secular clergy and laypeople—-Christ’s sacrifice as the marriage of the Son with the Church, and the devil. Book Three consists of thirteen visions, broadly covering the history of salvation from the Fall to a dramatic vision of the Last Judgement; it ends with a symphony of praise. Hildegard then wrote, from 1158-63, the Liber Vitae Meritorum, The Book of the Rewards of Life, with the theme of virtue and vice.

The final work of her trilogy is the Liber Divinorum Operum, The Book of Divine Works, which was completed in 1173. This work deals with the

manifestation of divine love in creation. Hildegard uses literal, allegorical and tropological readings of the Prologue to the Gospel of John and the opening of Genesis. In it is the City of God surrounded by the wheel of eternity with the love of God as its centre. Hildegard is better thought of not as a mystic, but as a visionary and as a prophet. Classical definitions of mysticism emphasise the union of the soul with God and the whole system of ascetic and contemplative disciplines that aim to facilitate that vision. Hildegard, however, did not follow this path. ’Prayer,’ to her, meant essentially petition and praise, expressed in liturgical form—-while ‘the love of God’ meant reverence, loyalty and obedience to God’s commands. To attempt to convey both the substance and the richness of Hildegard’s theology we have to contemplate her visual images and her music. Her visions are conveyed in startling immediacy in the illuminations of her manuscripts. She describes and then interprets these illuminations. Hildegard is not a systematic theologian; she was not interested in its aims. As one writer said: Her writings need to be read slowly and be ruminated upon, to allow their rich symbolism to permeate the imagination of the reader. Hildegard invites us to enter into a different outlook or vision upon the world, encouraging us to come to see what she “sees”: a world that is deeply sacramental, permeated and vibrant with the power of divine goodness, in which all things are interconnected. As Patricia Zimmerman Beckman notes, Hildegard’s visions seek not simply to describe but to induce revelatory experience in her readers. Hildegard, she comments, lives ‘in an integrated world where winds, herbs, celestial music all reveal an incarnational God.’ Her visions ‘serve as a handbook of God’s illuminating power throughout all creation.’ 4 A woman of her time, Hildegard, in her heroic individuality, strove to develop her intellectual and spiritual gifts and to fulfil her vocation, despite great obstacles. As a woman, she became a rare public figure who was esteemed and eagerly sought after. She, and a few others of her generation, were more learned than women would be again until the Renaissance. She has bequeathed to us many gifts.

Footnotes:

1 p. 148, Van Nieuwenhove

2 p. 9, Barbara Jane Newman, Classics of Western Spirituality

3 p. 12, Barbara Jane Newman

4 p. 152, quoted in Van Nieuwenhove

Sources:

An Introduction to Medieval Theology, second edition, Rik Van

Nieuwenhove, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Medieval Women’s Visionary Literature, edited by Elizabeth Alvilda Petroff,

Oxford University Press, 1986.

Hildegard of Bingen: Scivias The Classics of Western Spirituality, Preface

by Caroline Walker Bynum, Introduction by Barbara J. Newman, Paulist Press,

1990.